Metalcrafters on Mars

Haas Helps Take Former Sheetmetal Shop to Mars

Imagine this, you’re playing a round of 18 in Pasadena, California. It’s the final hole and you check the tee-box monument for particulars. It’s a tricky Par 4. Unfortunately, the hole is located in the center of a green only seven inches in diameter… more than 1360 miles away, in Houston, Texas.

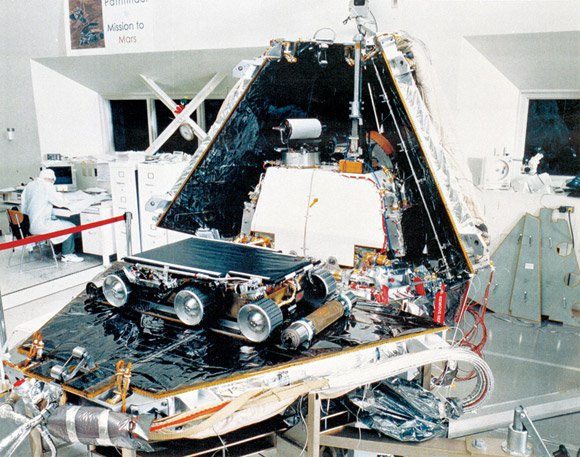

Though this scenario sounds impossible, it is exactly the situation faced by the navigation team of the Mars Pathfinder mission. For their game of interplanetary golf, Earth was the “tee box,” the “yardage” was 309,081,764 miles and the “hole” was a 15-mile diameter spot above the atmosphere of Mars on July 4, 1997. The navigation team planned the voyage as a “Par 4,” with only four trajectory corrections between Earth and Mars. They did, however, reserve the option for a fifth stroke within the final 24 hours in case of a bad game. The final stroke was unnecessary, though, as the navigation team successfully made par and landed the pathfinder in the hole on July 4, 1997.

Two years ago they were just another batch of parts for the machine shop. Sure, the blueprints were from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, but Norm MacKenzie thought nothing of it. He had done numerous jobs for JPL during his 25 years as a machinist.

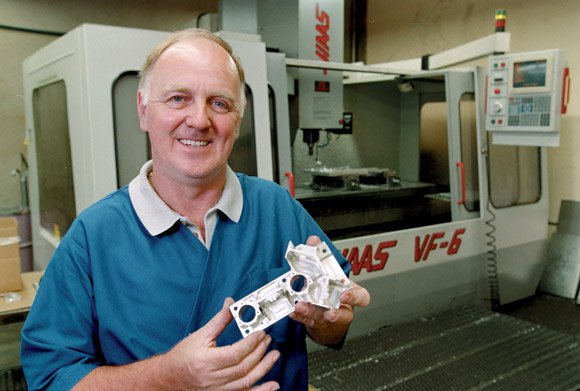

On July 4, 1997, however, MacKenzie proudly became a part of American history when NASA’s Mars Pathfinder module landed on the surface of the distant red planet. You could say he was partially responsible for the success of the mission. For, deep within the intricate confines of the Pathfinder module, those same parts he machined two years ago held the electronics for the main guidance system that led the Pathfinder successfully to Mars.

“At the start they were just another set of parts,” MacKenzie explained. “But the more we got into it, and started talking to the engineers, we realized they were going to Mars, and it was going to take seven months to get there. The culmination was watching the landing on television. I’ll be honest with you, I was a little nervous. I wanted to make sure the Pathfinder landed. That was a big thrill when I watched that. But it started as just another job.”

It may have been just another job, but it was a job that Metalcrafters of Simi Valley, California, couldn’t have taken on a few years ago. It took the addition of CNC machining centers and a skilled machinist – Norm MacKenzie – to take them to Mars.

For the past 22 years Metalcrafters has made their mark on the world by manufacturing close-tolerance, precision sheetmetal enclosures for a variety of industries – from NASA to Disney. For most of those 22 years, Metalcrafters didn’t have much of a machine shop to support their sheetmetal business. “What we had, basically, was a couple knee mills with controls,” said Scott Stewart, Metalcrafters’ General Manager. “We machined out of necessity – doing only what we had to – and sent out the rest.”

About five years ago, Metalcrafters realized they could create more of a seamless operation – going from sheetmetal to machining to welding – by bringing their machining processes in-house. It would give them more control over lead times and quality, and allow them to better serve their customers. Unfortunately, their old equipment didn’t have the capability or capacity to meet their growing machining needs. They purchased their first vertical machining center to meet the increasing demand.

It quickly became apparent the VMC could machine parts faster and more accurately than the old knee mills. “We kept the knee mills,“ Stewart said, “but it was kind of like having a new Cadillac and an old Chevy – nobody wanted to run the old machines. They could cut three-times as fast on the VMC.”

The success they found with the VMC got Metalcrafters’ management thinking. “We realized that, not only could we support our sheetmetal operation, but maybe we could make money at machining as well,” Stewart said. At that time, however, their only machinist worked part-time and had limited training. If the machine shop was going to be profitable, they needed a full-time, skilled operator to run the machines. That’s when they hired Norm MacKenzie.

Originally from Scotland, MacKenzie has been cutting chips for m o re than 25 years. Despite 21 years in the States, his Scottish brogue is still quite evident. As far as he’s concerned, though, he’s an American through and through.

MacKenzie took over the helm of Metalcrafters’ machine shop four years ago. Since then, they’ve added a new machining center almost every year. The last two machines added were a VF-2 VMC (30” x 16” x 20” travels) and a VF-6 VMC (64” x 32” x 30” travels) from Haas Automation

“We’ve bought about a mill per year, which has been a very reasonable growth rate,” Stewart said. “Whenever we add machines we look at adding two things – capacity and capability. We look at adding capacity, so we can get more work out the door. We look at adding capability, so we can take on more difficult jobs.

“Our goal was never to be a machine shop, but that’s basically what happened. The work was there, and we had the capability and the capacity. We’ve gone from machining out of necessity, to building a more seamless operation with the sheetmetal shop, to doing 65-70 percent straight machining jobs.

“If we were just supporting the sheetmetal shop and not taking in all this outside work, we could pro b a b l y still get by with one, maybe two, VMC ’s. But some of the same customers buying sheetmetal are buying machined parts also. It’s like one-stop-shopping.

“Disney is probably a classic example,” Stewart said. “If they can’t get their sheetmetal and machining at the same place (a lot of their stuff gets both, then gets welded) they’ll go someplace else. When they want to put a ride together they are n ’t always willing to wait. They need their parts, and they need them now. You’ve got to be able to deliver the finished package.”

MacKenzie agreed. “A lot of companies are doing that now – Lockheed, McDonnell-Douglas, Rockwell – as a way to maintain quality control,” he said.

Increased demand for machined parts prompted Metalcrafters to invest in additional CNC equipment. They chose a Haas VF-2 vertical machining center to expand their capacity. “We needed a machine to get more work out of here,” Stewart said. “We heard a lot of good things about the Haas machines, so we looked into them. We liked what we saw, and bought one. It was a reasonably priced machine that was going to help us increase our capacity.”

With all his machinists busy making parts on the other machines, the task of setting up the first job on the Haas fell to Stewart.

“I was surprised how easy the control was, it’s very self-explanatory, ” Stewart remarked. “Within half an hour I guessed my way through the control and set up the job. You can basically look at the control and understand it, especially if you’ve been on another machine. I’d say it’s more user-friendly than any other control . ”

“The keyboard is so simple, the way it’s designed,” MacKenzie added, “everything has its own little section. That’s what makes the Haas so easy to run. We do a lot of multiple fixturing, and the Haas lets you load multiple fixture offsets and multiple tool offsets quickly and easily. On our other machines you’ve got to physically punch the number in, which increases the chance of mistakes. With the Haas, you just punch one button to enter the offset , then another to go to the next tool. The Haas also has better performance – the tool changer, point-to-point with the turret, spindle orientation – these things are all faster, which saves a lot of time. We’ve been able to reduce cycle times quite a bit with the Haas. And it’s very accurate, I can hold two-tenths all day.”

According to Stewart , Metalcrafters is always looking to increase their plant’s capacity and capability. The VF-2 allowed them to increase their capacity and pump more parts out the door. But as jobs rolled in with larger production runs and bigger parts, they needed to expand their capabilities by adding a larger machine. They chose a Haas VF-6 with 64” x 32” x 30” travels, and their investment soon paid off .

We had a job for Disney that was too large to cut on our other machines. It was a heat-treated casting of ductile iron that was 20 inches tall. Every surface had to be machined, and we had to drill and tap holes, including blind holes at the bottom of the part that could only be reached from the top. The VF-6 was the only machine we had that would cut it, and cut it right.

Scott Stewart

Bigger parts, however, are not the only reason for having a bigger machine. Sure, there are times when a bigger machine is the only way to cut the part. But longer travels can also help you be more efficient, by allowing multiple set-ups so you can get finished parts off the machine.

“Travels are very important with multiple fixturing,” Stewart said. “That’s where the VF-6 has been really good. Some people look at travels and think ‘Well, my part is small, it will fit in a small travel.’ But with small travels you’re limited to performing one machining operation at a time, or cutting one side of a part. More travel can help you be more efficient by allowing multiple fixture s and operations. The set-up may take a little longer, but the customer is getting finished parts in a couple days instead of weeks. Now, I’m servicing the customer. ”

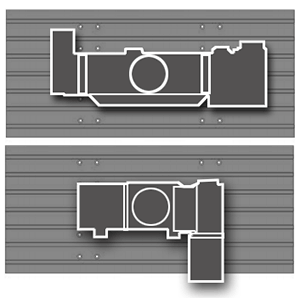

One customer who needed parts quickly was NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “We had done a few sheetmetal jobs for JPL in the past – a little thing here, a little thing there. Then all of a sudden a job pops up where they need it, and they need it now. They realized we were doing machining and gave us this aluminum panel to do. We didn’t even know what it was for, you couldn’t tell. Then they gave us another panel, then four more. It wasn’t until later that we found out everything was going into the Pathfinder,” Stewart said. “They needed parts fast, and we made it happen.”

Norm MacKenzie’s extensive experience and the versatile capabilities of the Haas machines are the key ingredients that made the JPL jobs happen.

Typically, JPL would send a blueprint to Metalcrafters. MacKenzie would look over the blueprint and start machining the part – usually writing the program right at the control. Since these were R&D parts, MacKenzie would often discover things that weren’t right. So, working hand in hand with the engineers, he would make changes until he had a finished part. Then he’d ship the part to JPL, w h e re the engineers would test it, make more changes, red-line the blueprints and send them back. “They’d make changes and I’d just make another part for them,” MacKenzie said, “and another, and another, until eventually we came up with the final part.”

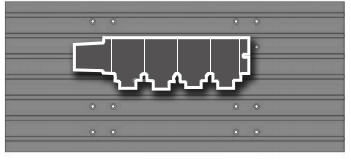

One of the most challenging JPL jobs, MacKenzie noted, was a small part designed to hold an array of six directional sensors for the main guidance system of the Mars Pathfinder module. Starting with a 9” x 9” x 3” block of 7075 aluminum, he machined an intricate web of pockets, ribs, holes and mounting tabs designed to secure the sensors for their 309-million-mile journey.

“It was a challenge because there were so many different angles and pockets in it,” MacKenzie said. “I’ve made a lot of fancy parts, but this was a little different, because of what it was, where it was going and what it was doing.”

MacKenzie opted to program the part directly at the Haas control rather than use a CAD/CAM program . “For me it was faster that way. I didn’t have the luxury of sitting and waiting for the program,” he said. “A lot of the part was very flimsy, with thin walls, so I had to be real careful and do a little bit at a time through MDI (manual data input). I couldn’t afford to get 70% into the part and lose it.”

MacKenzie used the Haas VF-2 with multiple fixtures to make three of the parts at a time, just in case he made a mistake. “There was a lot of work involved, and I couldn’t afford to lose the part . ”

The hard work payed off , though, when the Pathfinder successfully bounced to a stop on the surface of Mars. His parts had done their job and become a part of history. “It’s a thrill to see it up there,” MacKenzie explained, “a little part of me up there. I don’t know where Mars is, but I know it’s up there, and I’ve got a part up there, albeit that’s just a tiny part, but I’ve got a little part up there.”

One of the biggest things about the Haas machines is their versatility. We machine ductile-iron castings, 15-5 stainless, P21 stainless, 4130 steel, then we go to the different aluminium alloys. We run all sorts of materials. With the Haas, I don’t have any problems running aluminium then changing over to steel. A lot of machines can’t do that.

Norm MacKenzie, Jet Propulsion Labaratory