Titanium Hog Breeds Success

High on the Hogging

It was probably inevitable that Mike Bramlage would become a machinist. After all, he grew up in Dayton, Ohio, an area rife with machine shops serving the needs of the automotive industry . . . and his father was a veteran toolmaker.

Like many fathers, the elder Bramlage harbored hopes that his son might follow in his own footsteps. He didn’t force the issue, but when the time was right – and Mike couldn’t decide what he wanted to do – he gently steered his son toward an apprenticeship as a tool & die maker. The young Bramlage dutifully set off down the chosen path.

Mike learned the basics of machining under the watchful eye of journeyman machinists during the day, and under the fluorescent lights of the classroom at night. It was a thorough curriculum: how to select materials, choosing speeds and feeds, the dynamics of cutting tools, and the operation of manual mills, lathes and grinders. Mike hated it.

About halfway through his apprenticeship, the budding machinist packed his belongings and moved to Los Angeles in search of warmer climes. Upon reaching the City of Angels, Mike plied his trade at various machine shops throughout the area, honing his skills and further learning the trade. Machining was all he knew.

A mould shop in Costa Mesa kept the young Bramlage busy for about a year and a half, until a brief detour at the behest of a friend led him to Houston, Texas. Unfortunately, Mike landed in the Lonestar State just as the oil industry went bust, so jobs for machinists were few and far between. He did whatever work he could to make ends meet.

In 1984, Mike returned to the West Coast, this time a little further south to San Diego. Again, he relied on his skills as a manual machinist to survive. Again, he hated it.

It wasn’t until Mike discovered CNCs that he began to like his chosen career. “I hopped around a bit, working manual machines for a few years,” he says, “and then I went to work for a guy who trained me on the CNCs. It was a whole different world; everything was more interesting.

“Because I would work weird hours – weekend nights, weekend days – he put me on a new machine every week,” remembers Mike, “I got to learn all of the controls. I was on Mazaks, and Burgmasters, and Okamotos and Milacrons,” he says. “The Burgmaster was the first machine I learned.”

That shop was located in Santee, California, just west of San Diego, and it specialized in difficult work for the aerospace industry. “That’s all we did, the hard 4-axis and 5-axis stuff,” notes Mike. “We did anything and everything, and every machine in there was geared toward the harder work.” In fact, he says, the owner would actually turn down easier work in order to concentrate on the difficult jobs that no one else would do.

That philosophy stuck with Mike, and later would serve him well.

For the next 12 years, or so, Mike worked at the aerospace shop, expanding his knowledge and skills, and mastering just about every CNC in existence. At last he enjoyed what he was doing. He no longer hated machining.

But enjoying his work wasn’t enough. Mike wanted to learn more, so he took a job working nights at a shop that specialized in machining for the communications and electronics industries. They promised to teach Mike programming. “My whole goal was to learn,” he explains. “I had been a manual machinist, and I had been lucky enough to learn the CNC machines, but I wanted to learn another dimension.” Mike admits, however, that he had another reason for taking the second job: “All along I wanted my own shop,” he says. “The goal was to buy my own machine.”

Having operated nearly every CNC available, Mike knew what to look for in a machine. He also knew the kind of work he wanted to do. Like his boss at the aerospace shop, he wanted to take on difficult work that was challenging. To do so, he needed a machine that would handle anything thrown its way. “You don’t know what parts are going to arrive week by week,” Mike explains. “I was looking for a machine that could do anything.”

Because he was just starting out, price was a major factor. “I worked at two jobs for about three years, holding on to money because I wanted to buy a machine,” he says. “Once I reached the point where I was ready to buy, I looked at the Haas machines and the Fadals, because they were what I could afford back then.”

As luck would have it, the shop where Mike worked nights ended up purchasing both brands of machine during his tenure, so he was able to compare them head to head. “In my mind,” Mike notes, “the Fadals were for aluminium only. We pretty much had a rule in-house to only use endmills 1/2″ or smaller. Then they brought the Haas machines in, and it was like night and day. After an hour on them I said, This is the one I’m going to get.”

Mike made the leap to independence in January of 1998, buying a Haas VF-3 vertical machining centre. He quit his day job, but continued working nights to supplement his income while he built his own customer base. The VF-3 was installed in a small 1,100-square-foot shop, and Mike began doing overflow work for a former employer. Thus was born MB Manufacturing and Tooling Corporation of Santee, California.

Less than a month later, Mike’s friend, Chris Miller – a programmer he had worked with during his stint at the aerospace shop – hooked Mike up with a company in Los Angeles that manufactured aftermarket service parts for helicopters. One of the parts – a rotor blade component – was machined out of solid titanium. They needed help roughing out the raw blocks, and they needed it right away.

This posed somewhat of a dilemma for Mike. From the start, his goal for MB Manufacturing and Tooling was to take on jobs that were challenging and interesting, and deliver the parts on time and without rejects. The titanium helicopter part definitely fit the criteria, but his one machine was already busy doing other work. If Mike wanted to maintain his on-time delivery, there was only one solution: buy another machine.

That Saturday, Mike contacted Mike Flower of Machining Time Savers (the local Haas distributor, now the San Diego Haas Factory Outlet), and explained his situation. Flower told him that if he wanted a machine in a hurry, there was a VF-2 in stock that could be delivered the following week. Mike said, “Yeah, do it,” and by Wednesday he had a new machine.

The rest of the weekend, Mike says, he worried about whether or not the machine could handle the job. “I had heard rumors about the older Haas machines, and I didn’t know whether it would last with the titanium.” He soon realized he needn’t have worried.

That titanium job set MB on the road to success, helping Mike build the business much faster than he had anticipated. In fact, he ended up with so much work so fast that he had to quit his night job. “It just exploded,” Mike explains. “I was working from early in the morning until midnight, or later. I couldn’t miss even one night at the shop.”

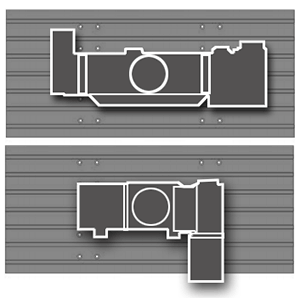

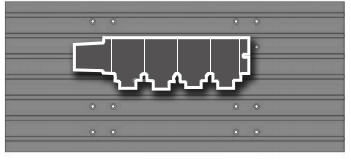

The helicopter part that started it all is called a titanium root fitting. In essence, it is a pair of contoured titanium “hands” that grip the main rotor blade and attach it to the rotor. There is a top and a bottom “hand,” and both are machined out of a single 8.5x9x1.5-inch block of titanium.

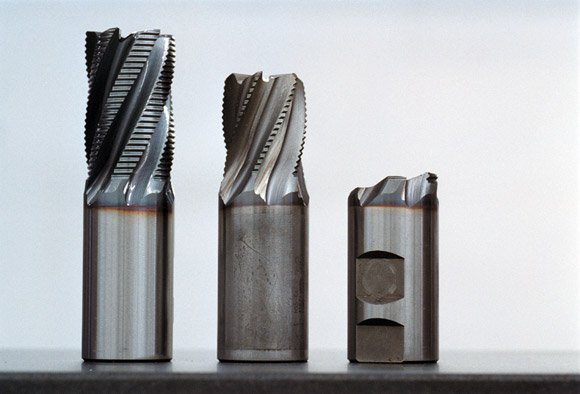

Initially, Mike was contracted only to perform the roughing operations on the titanium blocks. This entailed hogging out about 50% of the material with a 1.25″ roughing endmill, by far the most aggressive machining operation of the entire part.

Luckily for Mike, his customer had had problems in the past with other machine shops not delivering parts on time; so when Mike was able to deliver roughed blocks faster than the customer could finish them, the customer was quite pleased. It wasn’t long before Mike was given the contract to machine the entire part, as well as several other helicopter parts for the same customer.

Those parts kept Mike’s two Haas machines busy all year, generating gross sales of about $200,000 — not bad for a startup company.

With those kinds of numbers, Mike felt he could justify another machine if he continued getting new work. “And it just so worked out that my main customer just kept loading me with more and more work,” he says. So another Haas VF-2 was added, and during the following year, gross sales more than doubled to $500,000.

Hoping to continue the trend, Mike is already scanning the Haas product line for a new machine. “I figure adding another one is not going to hurt,” he says. His next planned acquisition is a Haas HS-1RP four-axis horizontal with pallet changer. “I think that will put me into a whole new line of work; I want to branch out a little.”

With success has come growth. MB Manufacturing and Tooling Corporation recently moved into a new 4,300 -square-foot facility. The equipment list now includes three Haas VMCs (one VF-3 and two VF-2s), a Haas 4th-axis rotary table, a small Brown & Sharp CMM, a manual mill and a manual lathe. Accord- ing to Mike, there’s still plenty of room for additional machines, and he made sure the new shop had enough power to accom- modate any future additions.

At the beginning of this year, Mike brought his brother, Matt Bramlage, on board to help run the machines (after about a year of constant persuasion). Like Mike, Matt has been a machinist since high school. The brothers also worked together at the aerospace shop before Mike set off on his own. Having shared many of the same experiences, they also share the same work ethic and desire to challenge themselves.

The programming tasks for MB have been handed over to Chris Miller, Mike’s friend who helped land the original helicopter job. Chris supplements his day job by doing programming from home after hours. Mike explains the arrangement this way: “I realized it was more cost effective to hire Chris to program on his off-hours. I make money when the machines are running. I don’t make money when I’m in here programming. He can write the programs and e-mail them over to me, and I can load them into the machines and start running parts.”

It’s a system that works well, allowing Mike to maintain his record of on-time delivery. At present, about three-quarters of his workload is comprised of helicopter parts, with the remaining 25 percent made up of jobs that walk in the door. “I’ve been lucky enough,” Mike reflects, “that I haven’t even had to look for work.”

The titanium root fitting is still one of MB’s primary jobs. Mike machines the part in four setups. First, a fixture holds the titanium block flat (at zero degrees), and a 1.25″ roughing endmill hogs it out to begin forming the contoured shape of the two hands. A pair of holes is then drilled through one of the hands, and a flat is milled on that same hand with a 1″ finishing endmill. The block is then moved to another fixture.

The second fixture holds the block at a five-degree angle (the job was programmed before Mike acquired his rotary table) so that the other hand can be machined. Again, holes are drilled and a flat is milled. The contours of both hands are then finished with a 1″ ballnose endmill, and the perimeter is cut in two passes, a roughing and finishing.

For the third operation, the block is flipped and mounted (again at zero degrees) in a fixture cut with the reverse of the parts. It is locked down through the boltholes, and a 1/2″ endmill is used to separate the two hands. At that point, one of the hands is finished. The other hand is then moved to a fourth fixture where a 1″ finishing endmill cuts the final flat on that part. Both hands are then deburred before being sent to the customer.

Mike wouldn’t reveal his actual cycle times for the parts, but did say that he could produce about a dozen root fittings a day. Of course, a day is a relative term. Mike doesn’t work your typical nine-to-five; rather, he usually works a full day, then goes home to share dinner and a little quality time with his family. Once the kids are in bed, he returns to the shop to run more parts.

Just because he takes a break, though, doesn’t mean his Haas machines do. Before going home, Mike makes sure the machines are loaded with parts, then sets them to run unattended. The Haas VMCs have a programmable coolant nozzle that automatically adjusts the coolant for each tool via the part program, so there’s no need for an operator to be present. This gains Mike several hours of additional machining that he otherwise might have lost. “Every night when I go home,” he says, “I load three machines and hit them on. I don’t have to worry about an endmill breaking, a drill breaking or a reamer running without any coolant on it. It’s amazing.”

MB has realized additional gains by optimizing his tooling and processes. For the titanium root fitting, for example, Mike researched several brands of endmill, talking to the manufacturer’s engineers about speeds and feeds, until he found the combination that worked best.

“The one brand I had the best luck with is OSG,” says Mike. “It’s just a regular one-and-a-quarter hogger, but it’s outperformed everything; it does about double what anything else does. I go half- to three-quarters width and about 3/4″ deep, and it can hog no problem. And the Haas machines have been able to hold the recommended feeds on all the endmills.”

For anyone who doubts the ability of the Haas machines to cut titanium, Mike has this to say: “That machine has been doing those (titanium) blocks for two years. The whole part hinges on hogging out with that one-and-a-quarter endmill, and it’s been hogging those things non-stop. I’ve got broken endmills out there.

“Looking back,” Mike explains, “the big thing in my mind is that, for a guy like me who buys one machine starting off, if the Haas hadn’t actually done what they claimed it would do, I’d have been dead; I’d have been under right then.

Well, MB Manufacturing and Tooling Corporation didn’t go under, and it’s a pretty sure bet that Mike now loves being a machinist. His father would be proud.